#35: On Malintzin and History

#35: On Malintzin and History

1 MARCH 2022

Malinche, or Marina, or Malintzin, was a woman at the crossroads.

If you grew up, like I did, getting Spanish homeschooled every summer, you know a little about her, but her story is glanced off of, especially in children's tellings of the conquista. She was Hernan Cortes’ slave, translator, and guide, as well as the mother of his child, but also an active participant and diplomat in the conquista. In the last month or so, I've been reading a lot about her, mainly in Margo Glantz's incredible edited volume, Malinche, Sus Padres Y Sus Hijos, which unfortunately has not been translated into English.

Malintzin was born in the Aztec empire, around the area we now know as Veracruz, in about 1500. Her father was a cacique, a leader of the community she belonged to. She learned the language of her family and her loved ones--likely some kind of nahuatl, because she was part of the ruling class. When she was a child, sometime around 8 to 12, her father died, and her mother remarried. Because her presence represented the possibility of political upheaval, her family gave her into slavery. From there, she was sold and traded up and down the gulf coast of Mexico. In her travels, she learned a few different dialects of Mayan.

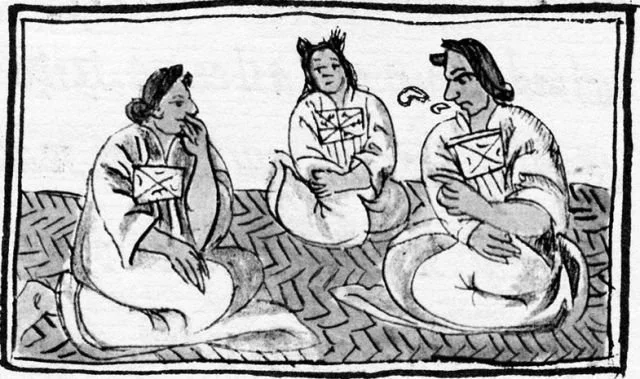

as a side note--I've always loved that speech in Nahua codices looks like little commas of breath coming from the speakers' mouth. Florentine Codex book X.

In about 1519, Hernan Cortés arrives in Potonchan, a Maya city in Tabasco. There was a battle, in which the Mayans suffered massive losses. As part of the settlement for peace, the Spanish received gold, food, and twenty enslaved women, one of whom was Malintzin. She, along with the other women, was baptized--she received the name Marina--and distributed to the men as servants and sexual objects.

At the time, Cortés had another interpreter traveling with him--Jerónimo de Aguilar--who spoke only Mayan. The first time they reached a population that spoke mainly Nahuatl, Aguilar was unable to translate...until Malintzin stepped in. I want to take a moment to note just how unusual this was for the time. Bernal Diaz del Castillo, the primary chronicler of Cortés' expedition, described the women native to the Mexican continent as being quiet, relatively withdrawn, meek. This could be a) racist claptrap; b) because most of the women they had regular contact with were and had been slaves who had been conditioned into meekness; c) because they did not speak the language, know the customs, or understand what the fuck was going on with their captors and we're quiet out of something like fear; or, d) be somewhat true, insofar as meekness and being withdrawn was culturally valued among women.

Not Malintzin though. For a while, she used Aguilar as a bridge translator, translating from Nahua to Mayan, and Aguilar from Mayan to Spanish, and back again. Before long, though, she picked up Spanish and began doing all the translations herself, directly. She translated the conversations between Cortés and Moctezuma at their first meeting in late 1519, and served as Cortés' translator all through the long conquest of that city for nearly two years. In 1522, her son with Cortés was born. From here, her life gets a little blurry. We know she eventually married one of Cortés' lieutenants, Juan Jaramillo, and had a daughter by him. It's unclear how long she lived, or what her life looked like after her marriage.

As you might expect, she's an incredibly controversial figure in Mexican history. In his book, The Labyrinth of Solitude, Octavio Paz calls her "la Chingada," or "the fucked one"--complicit in her own sexual humiliation, responsible for the violation of the entire Mexican nation. A somewhat bastardized version of her Nahuatl name, Malinche, has become an adjective, "malinchista," which you would call someone overly critical of Mexico. Some people say the legend of La Llorona, the woman who drowned her children for love of a man, is based on her. Her legacy is complicated, based on the thin sketch we have of her life by chroniclers who, I think it can be plainly said, didn't generally value the lives of indigenous women. Her actions are shaded by a complicated family past, mysterious motivations--was it survival or power or love or lust or a belief that she could make things better?

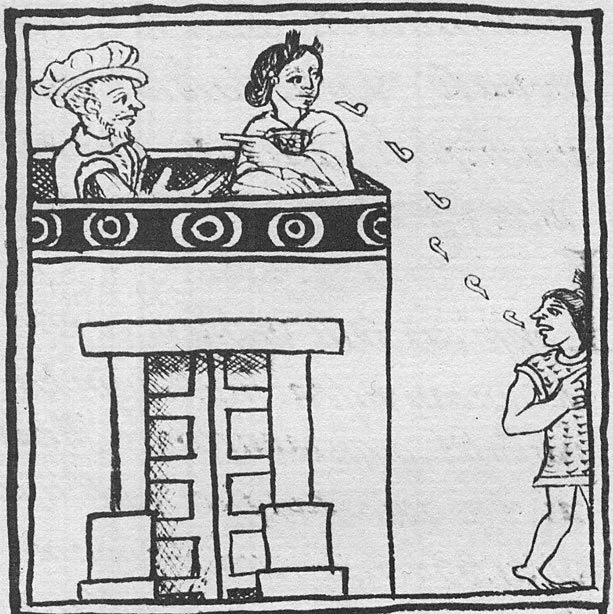

Florentine Codex Book XII

What I want to get into right now, though, are the ways that her identity and Cortés' became intermingled and crowded one on top of the other for the many long years she was his translator. In Spanish, Malintzin's is often called "la lengua"--the tongue--of Cortés. She was an extension of him, wrapped up in his body, held safe in his mouth. This is also how the erotics of translation, of the particular Cortés/Malintzin relationship come down to us. What is more interesting is that the opposite is also and perhaps more often true. Native people often called Cortés Malintzin--it was, after all, her voice, her presence that was the one negotiating, Cortés was just a man sitting in the shadows. What's even more curious, however, is that there are entire stretches in his Cronica in which Díaz refers to Cortés in the exact same way. Their duality--and more specifically, her charisma or power or something--was such that despite the thousand obstacles there were between them, mostly related to differences in age and race and class and language, she managed to eclipse Hernan Cortés. Every time I think about this it blows my mind a little bit.

The book I'm writing deals with translation, and the ways power moves through it. It also deals with love, and family, and empire and betrayal. I've been thinking through and with Malintzin's story for a few years now, but I also find myself really wary of saying anything about it that's definitive. There's so much you can read, or not read, into it. You can call it a story of total subjugation, in which a woman was forced to betray her people, endure sexual violence, and bear a child. You can call it a love story, in which a woman's love for her captor overturned a nation. You can call it a story of survival, or of greed, in which a woman does whatever she needs to in order to come out on top. For all that her voice rang out in the moment of her history, we have very little record of who Malintzin actually was, how she felt, how she moved through the world and why she made the choices she did--or even if she made them freely.

When I look at her story, the main thing I want to read into it is how utterly complicated it is to be a person, and how utterly complicated a person is. Even if we had a Woolf-esque level of journals, I don't think we'd ever be satisfied that we knew who Malintzin was, and I think if put into her situation, most people wouldn't actually be able to find a way forward that aligned with their values and their need for survival. What we can see clearly is the complicated, strange way power moves through relationships, how it crackles up and down the bridges between languages, and how one person's actions can change the world.