#28: Annie Dillard and Making Do

#28: Annie Dillard and Making Do

26 February 2021

I’ve been reading a lot of books about arctic exploration this month, in part because nothing makes me feel better about living in the snowiest Chicago in 40 years than reading Barry Lopez wax rhapsodic and tender about an even more unforgiving, spartan landscape.

Lopez, who passed away last year, was a writer known for his careful eye and deep reverence for the natural world. I had heard of him, but hadn’t read him before, and the outpouring of love and memorials from other writers I deeply admire made me put his books on hold at the library and work my way through them over the course of this month. I spent about half of Horizon being vaguely disappointed that Lopez was not, as I had thought, Latino—I hadn’t realized how important the idea of an older Latino man, puttering around the margins and extreme climes of the world was to me. This was kind of compounded by Lopez’s sympathies throughout for colonizers like Capt. James Cook (he insists throughout that he didn’t really mean it, it being I guess the exploration that would lead to colonization attempts across the Pacific), but by the time I got to Arctic Dreams, one of his earlier and most famous books, I was ready for reading Lopez. It’s a lot of careful analysis of biology (narwhal’s tusks only spin counter-clockwise, this is what a polar bear’s year looks like) and history (here is the camp of one arctic explorer or another, here is how he met his hubristic doom not far from this spot) punctuated by moments like this one:

There is a word from the time of the cathedrals: agape, an expression of intense spiritual affinity with the mystery that is “to be sharing life with other life.” Agape is love, and it can mean “the love of another for the sake of God.” More broadly and essentially, it is a humble, impassioned embrace of something outside the self, in the name of that which we refer to as God, but which also includes the self and is God.

Yes! All this, of course, put me in mind of one of my favorite essays on both God and Arctic exploration, Annie Dillard’s “An Expedition to the Pole.” I can’t find a version of it online, but you can find it in her book Teaching a Stone to Talk. In it, she compares early British expeditions to find the North Pole to a church service in which we are seeking to find “the Absolute.” Both are encumbered by these silly little oddities we are fully convinced we need: a priest’s creaky knees and an out-of-tune worship service leader or sensible, thin wool coats and silver with the family crest on it. In either case, we are absolutely unprepared for the sheer terrifying scale of what we are setting out to find. Of the explorers (and of us, in church) she writes “they man-hauled their frail flesh…their sweet human absurdity to the Pole.” In a landscape so often described as austere and sublime and eternal, here they were, the Brits, putting on plays and getting sick and writing spare, dignified letters where there was barely room for survival, much less dignity.

As I mentioned, we are in the snowiest Chicago in some 40 years, and after we got some 2 feet of snow the weather did not rise above freezing for a week so, of course, we stayed inside. It’s a moral imperative, you might know, and we’d been doing pretty well at it, but you don’t realize how much you come to rely on your little trips to Walgreens for the snacks or on letting the dog haul you halfway around the neighborhood on his morning walk (which he somehow doesn’t feel like doing when the snow comes up to his little puppy chin). There’s been a lot of talk of hitting the pandemic wall lately—my own bout with COVID was a year minus two weeks ago, ditto the last day I went into an office—but for me those facts tumbled over and alongside the weather into an annual crisis that was worse than most years.

Every year, I swear to myself I’m prepared for it, I know what’s coming, I dutifully eat my little salmon toasts and take my vitamin D supplements and park myself in front of a SAD lamp like a recalcitrant houseplant, and somehow, every February, I feel like I’m simply going to explode if I don’t escape from my whole entire life and go into the desert until every part of me that is cold or sun-starved just evaporates into mist. This year, I literally planned trips to the desert—applying for funding for research trips to take me to the Arizona desert around Tucson, looking at artist residencies in Ajo for the fall, when I am hopefully vaccinated—and when that failed, just played Candy Crush without blinking for about a week straight.

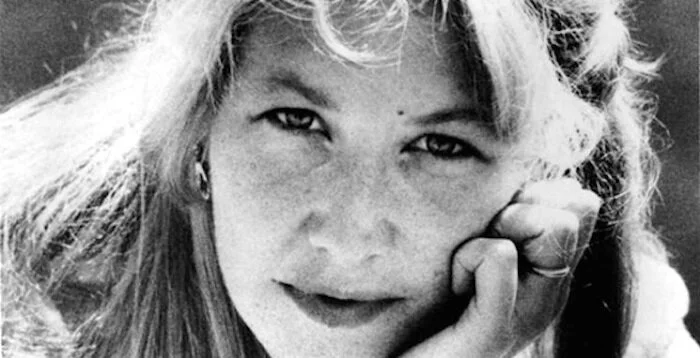

I can’t believe I haven’t written about Annie Dillard here before—she’s one of the authors that someone once described as one of my two cathedrals of Ann- (Anne Carson is the other)—but I’m glad I’m doing it today. Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Dillard’s debut prose book and a Pulitzer prize winner, was written when she was my age, 28, and living in a Virginia suburb with her husband—none of which make it into the book itself.

In her accounts of her walks around her neighborhood, she is a lonely roving eyeball, looking for God in the emptiness and fullness that is nature. She was worried that no one would be interested in the memoirs of “a housewife from Virginia named Annie,” so she became a pilgrim, an anchoress, a monk in the woods, leaving out all her domestic trappings, giving in literature her life a shape of loneliness and quiet and . The book is structured through the seasons, but also has a theological structure: first, a cataphatic spring into summer, in which life multiplies and evolves into millions of wriggling creatures, the ooze and the skittering legs enough to make your shoulders creep up around your ears, and then into the apophatic fall and winter in which life is pared away into silence—a silence like the Absolute, a silence that is God, a God she finds, once again, in “sharing life with another”—the natural world, that is.

Here’s the lessons I take from Dillard in this apophatic season as things get pared away, when the stuff that makes up my life feels uninteresting and tired and constricting, like the only way I will ever make anything of myself is to jet off into the wilderness: there is enough here to build a life, enough creeping skittering things in the empty lot behind my apartment to remind me that spring is coming, enough wildness in my own four walls to contain me.